In the realm of mine closure and asset transition planning, what lies hidden within a drillhole can often be a greater concern than what is immediately visible on the surface. The unseen conditions within these small, seemingly insignificant voids can lead to substantial environmental and safety risks if not properly addressed. This is where the concept of “thinking small, acting large” comes into play: minor yet deliberate actions, can have a significant impact on broader environmental and safety objectives.

These remnants of exploration and mining activities are sometimes overlooked but have the potential to become serious hazards over time. Case studies, such as those from Fitzgerald River National Park and a recent mine closure project, reveal the hidden dangers and unexpected challenges that inadequately managed drillholes can pose, from faunal entrapment to extensive rectification work needed for regulatory compliance. By ensuring drillholes are securely sealed and rehabilitated, significant progress can be made toward a more sustainable and environmentally responsible future. This approach aligns with global initiatives such as the Global Biodiversity Framework and the pursuit of Nature Positive outcomes.

Regulatory Landscape: A Global Perspective

Globally, the management of drillholes whether during exploration, production, or closure has become a critical focus in the mine life cycle, with many countries implementing stringent regulations to prevent long-term environmental and safety hazards. From Canada to South Africa, regulatory frameworks are being updated to ensure that drillholes are adequately sealed and rehabilitated, mitigating risks associated with ground instability, contamination, and other hazards. However, these regulations often vary in scope and enforcement, leaving gaps, particularly when dealing with legacy drillholes.

Australian Context: Guidelines and Challenges

In Australia, each state and territory has exploration-related guidelines for sealing and rehabilitating drillholes, developed mainly since the 1990s. These guidelines often do not cover the vast number of legacy drillholes created before modern regulations or under lower standards. Even drillholes rehabilitated to past standards can degrade over time due to factors like sealant breakdown, ground movement, corrosion, erosion, and environmental changes (Commonwealth of Australia. (2014). These issues threaten long-term integrity and pose safety and environmental risks.

Safety Implications of Inadequately Secured Drillholes

Drillholes that are not properly secured or rehabilitated can present several safety hazards:

- Human Risk: Unsealed drillholes can be hidden by vegetation or debris, posing dangers to mine workers, residents, and visitors, potentially leading to severe injuries.

- Vehicle Damage: Drillholes near roads or pathways, or even remote areas can pose risks to vehicles and their occupants. Protruding drill stems or collars, often hidden by vegetation, add to the danger.

- Gas Emissions: Boreholes drilled in coal seams or other gas-rich formations can continue to release hazardous gases, such as methane, if not properly sealed.

- Liability Issues: Mining companies may face legal and financial liabilities if accidents occur due to inadequately secured drillholes.

Environmental Impacts of Poorly Rehabilitated Drillholes

Improperly rehabilitated drillholes can have significant and potentially far-reaching environmental consequences:

- Faunal Pit Traps: Unsecured drillholes can trap small mammals, reptiles, and larger animals, causing injury or death and disrupting local ecosystems.

- Groundwater Contamination: Unsealed drillholes can allow contaminants to reach groundwater, particularly in mining areas with hazardous substances, affecting water supplies for humans and wildlife.

- Aquifer Mixing: Drillholes that penetrate multiple aquifers can cause mixing, leading to contamination (e.g., increased salinity) and disrupting natural groundwater flow and levels, affecting water availability and quality.

- Habitat Disruption: Inadequately rehabilitated drillholes and associated infrastructure can alter natural habitats, causing soil erosion, changes in vegetation patterns, and degradation of local ecosystems.

Case Study: Fitzgerald River National Park

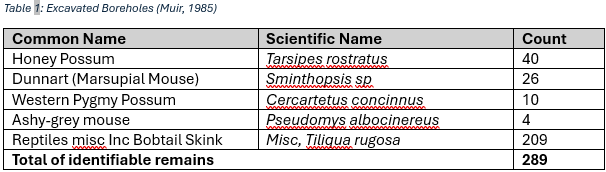

While more modern research may exist, the findings from two boreholes left from mining exploration in the Fitzgerald River National Park in 1980 provide a stark example of the environmental impact of inadequately rehabilitated drillholes. According to an internal report by the Department of Conservation & Land Management (Muir, 1985), the boreholes were likely open for several years. The report observed a high proportion of teeth among the skeletal remains, indicating significant fauna entrapment. Table 1 below presents the identified remains.

The Magnitude of the Problem: A Global Perspective

The issue of inadequately secured and rehabilitated drillholes is not limited to any specific region; it is a global concern. Estimating the total number of drillholes worldwide is a complex task, with many gaps in data and varying standards for reporting. However, a focused effort in Australia to collect drillhole data from state and territory government agencies responsible for managing their respective databases has provided some insight into the scale of the problem.

Based on this data collection process and additional sources, including Schodde, R. (2022, July 12), as well as conservative extrapolation to cover periods not included in current databases, it is estimated that there could be well over ten million drillholes drilled in Australia alone. While a sizeable portion of these drillholes may be capped and secured, many others are likely to remain inadequately rehabilitated, posing ongoing risks to both safety and the environment.

The sheer number of drillholes in just one country highlights the global scale of the issue and underscores the critical need to address even seemingly minor concerns like drillhole management as part of a broader commitment to environmental sustainability and safety.

Case Study: Recent Mine Closure Project

In a recent mine closure project in central Qld Australia, initial records indicated that over 4,000 mine development and exploration drillholes existed within the mining leases, but the status and condition of these drillholes were poorly documented. During the mine’s detailed closure planning phase, a comprehensive audit was conducted to verify the location and status of all these drillholes. This audit uncovered that approximately 1,500 drillholes required some form of rectification work, including critical tasks such as redrilling and grouting, collar removal, drill pad reshaping, and revegetation.

The discovery that such a significant number of drillholes needed treatment necessitated a substantial fieldwork program that had not been accounted for in the preliminary closure planning. This unexpected scope of work required mobilising a drilling and grouting crew and a civil earthworks crew to establish access and carry out the necessary rehabilitation activities.

The case highlights how easily remote and seemingly minor disturbances can be overlooked or underestimated during initial closure planning phases, leading to unexpected costs and extended timelines. Moreover, it serves as a critical reminder that even when records indicate that drillholes have been sealed, a thorough re-audit during the closure phase can reveal substantial gaps that must be addressed to ensure environmental, safety and regulatory compliance.

Linking Mine Closure Practices to Global Biodiversity Goals

Properly securing and rehabilitating drillholes is vital for environmental protection, safety, and aligning with global sustainability frameworks like the Nature Positive initiatives and the Global Biodiversity Framework. These frameworks aim to halt biodiversity loss and promote a net positive impact on ecosystems through sustainable management practices.

Key Alignment Areas:

- Ecosystem Protection: Proper management of drillholes prevents hazards to wildlife and contamination of ecosystems, aligning with the Global Biodiversity Framework’s goals of reducing ecosystem degradation and enhancing habitat resilience.

- Safeguarding Groundwater: Sealing and rehabilitating drillholes reduces aquifer mixing and contamination, supporting groundwater protection and maintaining biodiversity and ecosystem services.

- Preventing Biodiversity Loss: Addressing risks like faunal entrapment and habitat fragmentation supports Nature Positive goals to halt and reverse biodiversity loss by minimising impacts on flora and fauna.

- Supporting Global Conservation Efforts: Responsible drillhole management aligns with global strategies, such as the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework, by reducing human impacts on nature and meeting international sustainability commitments.

By incorporating these principles into mine closure strategies, companies can align with international environmental standards, mitigate risks, and demonstrate a commitment to global biodiversity and ecosystem health.

Conclusion

Mine closure planning presents an opportunity for the mining industry to “think small, act large.” By addressing the specific issue of inadequately secured drillholes, companies can significantly enhance safety, protect the environment, and support biodiversity. Effective drillhole management aligns with global initiatives like Nature Positive and the Global Biodiversity Framework, contributing to a net gain for nature and a sustainable future.

Targeted actions, such as securely sealing and rehabilitating drillholes, demonstrate how small steps can lead to substantial positive outcomes. Integrating these practices from exploration through closure helps prevent hazards and minimises long-term environmental impacts.

References

ABC News. (2011, Sep 29). Tassie devils face mining hole death traps. Retrieved from ABC News: https://www.abc.net.au/news/2011-09-29/20110929-devil-death-trap-fears/3037972?site=northtas

Commonwealth of Australia. (2014). Bore integrity, Background review. This background review was commissioned by the Department of the Environment on the advice of the Interim Independent Expert Scientific Committee on Coal Seam Gas and Coal Mining. The review was prepared by Sinclair Knig. Retrieved from https://www.dcceew.gov.au/sites/default/files/documents/background-review-bore-integrity.pdf

Ellis, M. V. (2013). Impacts of pit size, drift fence material, and fence configuration on capture rates of small reptiles and mammals in the New South Wales rangelands. Australian Zoologist, 36(4), 404-412. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.7882/AZ.2013.005

Muir, B. (1985, August). Library W.A Department of Conservation & Land Management. Retrieved from re: Impact of mineral exploration bore holes on fauna: https://library.dbca.wa.gov.au/FullTextFiles/C20078.pdf

Schodde, R. (2022, July 12). Overview of the Australian Drilling Market. Presentation at the AusIMM Diamond Drilling Workshop, Avoca, Victoria. MinEx Consulting. . Avoca, Victoria, Australia: Retrieved from AusIMM-Drilling-Workshop-July-2022 (2)-Copy.pdf .https://minexconsulting.com/overview-of-the-australian-drilling-market/

G. Wells (n.d.), Permission granted by Botanic Gardens and Parks Authority, image sourced from Lloyd M. V. Barnett G., Doherty M. D., Jeffree R. A., John J. Majer J. D., Osborne J. M., Nichols O. G. (2002). Managing the Impacts of the Australian Minerals Industry on Biodiversity. ACMER 2001. pp. 114. Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/234066344_Lloyd_M_V_Barnett_G_Doherty_M_D_Jeffree_R_A_John_J_Majer_J_D_Osborne_J_M_Nichols_O_G_2002_Managing_the_Impacts_of_the_Australian_Minerals_Industry_on_Biodiversity_ACMER_2001_pp_114